|

A shorter version of this essay was featured in "Maine Bicentennial Community Cookbook".

Maine curates its brand identity: "The way life should be." It is grounded in a back to nature movement articulated in the Nearings’ book "Living the Good Life.” Before the Europeans’ arrival, the people indigenous to this land spoke of their "good life." Each Wabanaki tribe had a word or phrase that expressed the collective wellness of a thriving community. Always at the center was food. Food gathers us. We organize around sources of food, seeking simple ways to nourish ourselves. When Wabanaki people met French explorers in 1604, they helped those early settlers to survive the winter at St. Croix. They greeted them with an ethic of sharing and gratitude for what the land and sea provided. Instead of learning the natural cycles of this new place, these first immigrants began to compete with the people living here and impose their priorities and values. Eventually, they displaced them from their homes, interrupted their relationships to the earth and disrupted their self-sufficiency. To justify land theft, murder and other crimes, these colonizers convinced themselves that the peaceful people here were somehow less human than Europeans. This ideology of superiority remains the foundation of inequality and maintains food insecurity today. Maine people are seen as resilient, as we have to be, facing harsh and changeable conditions on land and sea. There was a time we, collectively, addressed far more of our local food needs than we do today. The modern food system now provides much for us, bringing fresh and packaged foods great distances, distributed through super markets, before they arrive on our tables. Still, people struggle to feed their families for reasons common 400 years ago, 200 years ago and today. Bad luck, poor health, unexpected expenses and a tough winter are among the obstacles of getting enough good food to thrive and be healthy. Over 30 years ago, a serious discussion began that if we are to solve the problem of hunger, we need to measure our progress toward that end. In the mid 1990s, the US government adopted the term “food insecurity” to assess and explain poverty related food deprivation. The US Department of Agriculture defines food security as “access by all people at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life.” Each year, through the Census Bureau, the USDA conducts a survey to assess the extent to which U.S. households struggle to get adequate food. In September 2019, the USDA released its 24th annual report on Household Food Security in the United States. It estimated 11.1 percent of American households were food insecure, that is, they lacked enough food for all household members. Maine had an overall food insecurity prevalence of 13.6 percent and more concerning is the approximately 33,500 Maine households (5.9%) experiencing very low food security (VLFS), significantly above the national average on both counts. In this survey, only Alabama, Arkansas, Kansas, Louisiana, Mississippi and Oklahoma have a higher prevalence of VLFS than Maine. What should be obvious, but needs to be repeated, is that food insecurity results from inadequate income for a family to meet its food needs. Additionally, we have become disconnected from our food, no longer relying on our immediate environment to cultivate, forage, hunt or fish for the main sources of our diet. One answer lies in our local food resources. Local food supports nutritious diets, stimulates regional economies, sustains healthy environments and creates strong social connections. This means that increasing local production, processing and access can alleviate hunger through a variety of strategies while building a resilient and equitable food system. Local food is an important tool to build food-secure communities. Knowing the farmer who grows your food is one of the most meaningful things you can do to strengthen your community. We have forgotten how to appreciate our food. We don’t know where it comes from. We don’t know how to make it delicious and nourishing. We ignore the marginalizing effect when families do not have enough good food or the knowledge to prepare it. Does this mean our food system is broken? Or is it producing outcomes precisely as those who profit from processed foods that undermine public health would have it operate? My bias is that the place our food system needs most healing is where it prevents people from accessing healthy food. Beginning there, these separations need to be woven back together and made whole. Maine has a unique and historic opportunity to rally together and address this complex social problem. On May 21, 2019, Governor Janet Mills signed LD 1159: Resolve to End Hunger in Maine by 2030. Acknowledging our “Dirigo” motto and spirit, no other state has made a similar commitment. With support from the Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry, an advisory team presented its initial report to the legislature on March 3, 2020. It outlines the comprehensive strategy required to build food and economic security with Maine families. Ultimately, our country’s history of institutional racism is at the root of poverty and food insecurity. Economic and racial justice are inseparable. Any plan to end hunger must reference intentional policy choices in our past that resulted in disparate outcomes for targeted groups. The resulting economic inequality impacts not just people of color, but is the foundation supporting the poverty that afflicts everyone who can’t put nourishing food on their table. This poverty is a cost to and a burden on us all. It takes away the humanity of those who have enough, making us all complicit in an economic system that punishes people for nothing they did wrong. The honest stories told about who is poor and why reveal the causes and provide a framework for solutions. We must review historical moments when our communities made choices that privileged those already empowered to be more powerful while stripping others of basic necessities. Our children must learn a coherent story about why this nation and state allowed people to be poor. When we acknowledge that making people poor is a collective choice, our children’s history will tell how together we solved the problem of hunger. Jim Hanna has been a Community Supported Agriculture member of Willow Pond Farm in Sabattus since 1991. He has worked intentionally to strengthen Maine’s food system for almost thirty years. His children and grandchildren are blessed to be growing in Maine. Jim Hanna Executive Director Cumberland County Food Security Council [email protected], 207-939-3854

3 Comments

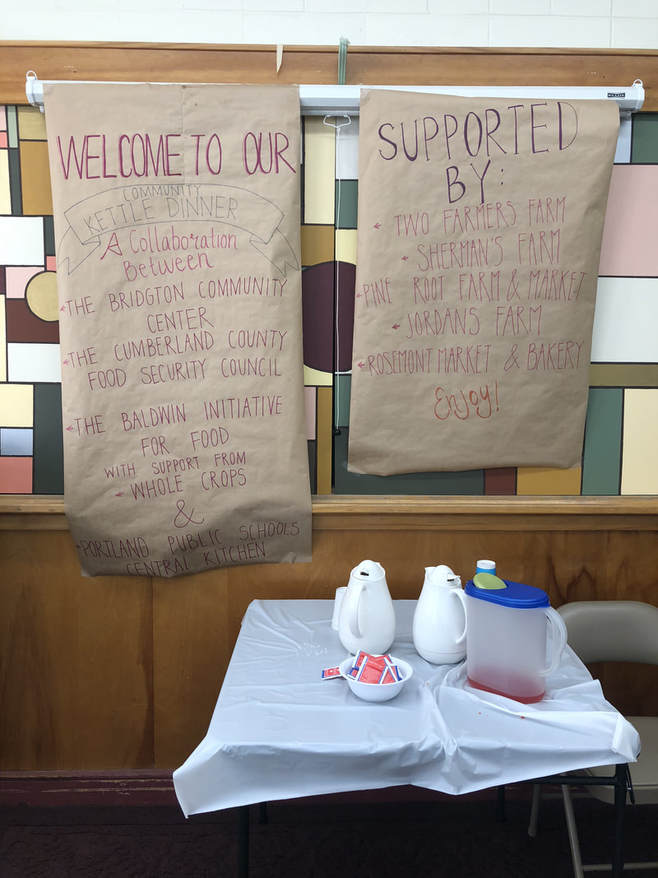

On August 2nd, we were delighted to co-host a Community Kettle Dinner at the Bridgton Community Center (BCC). The Community Kettle Dinner is a tradition at the BCC, and is held every Thursday at 5 PM. We collaborated with the Baldwin Initiative for Food, which serves Oxford and York counties, to share our gleaned produce to create a three course meal. As is the nature with gleaning, we did not know what we would have for ingredients until the day before the meal. It was a fun challenge to come up with recipes on the fly. The CCFSC gleaned cucumbers, zucchini, carrots, kale, and bok choy from our weekly produce pick up with Two Farmers Farm in Scarborough. Additionally, last month we gleaned strawberries with Jordan's Farm in Cape Elizabeth. To add to their shelf life, we processed them into preserves. We returned to Jordan's two days before the dinner and gleaned chard, summer squash, and yellow zucchini. Don Kauber, of the Baldwin Initiative for Food (BIFF), gleaned zucchini, tomatoes, and spinach from BIFF's weekly glean at Sherman's Farm. He went on to glean 64 ears of corn from Pineroot Farm in Steep Falls. Rosemont Market & Bakery donated loaves of day old bread to the dinner. Joined by two volunteers, the CCFSC team produced a dinner for 42 in just about three hours. For our first course, we served a panzanella salad using our donated bread and gleaned tomatoes, as well as a cucumber dill salad. This was followed by a main of an ear of corn, mixed sauteed greens, and koosa, a hollowed squash and zucchini stuffed with tomato, rice, carrots, onion, mint, parsley, and cooked in a tomato, garlic, onion broth. For dessert, one of our awesome interns took the reins and made a delicious strawberry shortcake! It was based off Nancy Harmon Jenkins' recipe, which has roots in Maine! We had a great time out in Bridgton and loved meeting new people, discussing gleaning and local food, and sharing a meal. Many thanks to the BCC, BIFF, our gleaning partner farms, our two AmeriCorps volunteers Haley and Ryan, and Portland Public Schools for letting us store our gleaned product in their cooler until it was ready to be cooked! The BCC is always looking for volunteer groups to collaborate on community meals. If your group is interested in volunteering, contact Carmen Lone at (207) 647-3116. Jim's Koosa RecipeVegetarian Koosa (Squash) in Tomato Broth

For every dozen summer squash/zucchini prepare the following stuffing; 1 cup rice 2 cups chopped vegetables (carrot, broccoli, bok choy) Can also include tomato 1 small-medium sweet onion 1/2 cup fresh herbs (mint, oregano, parsley) 1/2 cups greens (kale, spinach, etc.) 1 teaspoon salt 1/2 teaspoon black pepper 1 teaspoon allspice or cinnamon 1/2-3/4 cup oil Prepare the broth 1 1/2-2 lbs tomatoes, chopped 1 medium onion chopped 3-6 cloves garlic, peeled and quartered 1 bay leaf salt and pepper 2 TB oil or butter Water as needed Simmer broth ingredients as you core and stuff the squash Leave about 1/2 inch space in squash for rice to expand Pack squash upright and tight in simmering broth Add enough water to immerse squash and bring to gentle boil Return to simmer for 40 minutes, adding water to keep broth level at height of squash Let rest 20 minutes before serving Note: One pound of lean ground beef or lamb can be substituted for chopped vegetables On March 9th, the CCFSC held the first "Gleanhole Suppah" in the 409 Cumberland Ave community meeting space. The Gleanhole draws on Maine's traditional Beanhole Suppers with an emphasis on gleaning from root cellars as storage crops start to turn. Additionally, this event served as a reminder that local food is available all year round. The Gleanhole Suppah was made possible through many generous donations. Wandering Root Farm donated fresh local eggs, Maine Grains donated stone ground flour, Maine-Ly Poultry donated 40 pounds of turkey leg and thigh, and the Portland Food Co-Op donated day old bread and milk. We gleaned apples from Morris Farm, carrots from Two Farmers Farm, and cabbage and rutabaga from Jordan's Farm. Fork Food Lab generously allowed us to store our donations in their freezer space. With help from Garbage to Garden volunteers and SMCC culinary students, Chef Leavitt turned the gleaned and donated food into a wonderful meal of turkey meatballs, vegetable stew, roasted carrots, golden beets, ginger slaw, yogurt, and apple cake. Preble Street received the left over food from the event. Thank You to our Partners!(Click on a partner to be directed to their website!) By, Jim Hanna

Originally published 2/13/18 in the Portland Press Herald. I am grateful to hear Gov. LePage express concern for the well-being of people made poor by an economy that is not working for everyone. He demonstrates courage by challenging companies that poison people with unhealthy food products. His vision of better nutrition for Mainers is a goal that the Cumberland County Food Security Council shares. The governor recently said, “When we could no longer deny that smoking was causing suffering and early death for millions of people, the government finally stood up to Big Tobacco and did the right thing. The time has come to stand up to Big Sugar and ensure our federal dollars are supporting healthy food choices for our neediest people.” Search photos available for purchase: Photo Store →The Cumberland County Food Security Council believes that government should stand up to companies that prioritize profit over people. We agree that access to food with negative health impacts should be discouraged. But why limit the access of only poor people? Since all of us are subject to the seductive marketing and addictive nature of food infused with high-fructose corn syrup and sugar, it is right to consider prohibitions on those products for everyone. Households that receive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits purchase no more sweetened beverages than any other household does, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Let’s look at how we have reined in tobacco’s influence. Advertising for tobacco products is now illegal. People under 18 are no longer allowed to purchase cigarettes. How soon might we hear, “I’ll need to see your ID before I can sell you that Coke”? Taxes have been imposed on tobacco products. The money raised pays for message campaigns that portray the true health impacts of tobacco. Those taxes also invest in ways to prevent and address the negative health outcomes resulting from smoking. In 2013, there were no taxes on soda. Now, over 9 million people in the U.S. live with a soda tax. Collecting a penny an ounce for every pop sold in Maine would generate significant investments for public health. There are already many underfunded programs that create better health outcomes for low-income people. Many do that while paying local farmers and building Maine’s agricultural capacity. What additional solutions could we come up with if we unleash the imagination of Maine’s food entrepreneurs with significant resources available to sell more healthy local food to everyone? What a boost for our economy and our collective spirit! In this transition to a locally empowered food system, we will create jobs, make healthy food more affordable and make its production environmentally sustainable. This will create more access to good food and better health outcomes for people who currently run out of money to feed their families, either occasionally or often. If the governor’s concern for the nutrition of poor people is sincere, then he should reverse the loss of food benefits from intentional restrictions implemented by his administration. In December 2010, the month before he was inaugurated, there were 125,028 active food stamp cases in Maine, serving 243,301 people. By December 2017, the caseload had dropped to 93,602 cases and 178,193 individuals. While some left SNAP because of increased income, tens of thousands of people who are no longer eligible still need assistance putting nutritious food on their tables. Recent USDA food security research indicates Maine has had among the largest increases in hunger relative to other states. Cutting access to the SNAP benefits that a family needs is not an effective strategy for “supporting healthy food choices for our neediest people.” When it comes to children, particularly in the context of U.S. economic inequality, poverty has a huge impact. Families that live on much lower incomes than their neighbors will be alienated from the society around them, unable to participate fully in the community. Children growing up in families made poor by a dysfunctional economy will face permanent disadvantages. This is magnified when the family is of color, has a minority culture or religion or does not have English as their primary language. Targeting those households with restrictions on food that everyone else has access to just makes them feel more marginalized and more likely to act like they don’t belong. True leadership does not use its power to punish people who are already at the mercy of forces they cannot control. True leadership persuades us all to work together to make choices that elevate the common good. I hope Gov. LePage will work with us so that all eaters, not just those with limited food budgets, can benefit from a nutritional environment with more access to food that enhances everyone’s health. What we call our country’s “emergency” food system consists primarily of food banks, food pantries and soup kitchens. A food pantry hands out packages of food direct to people in need. If an establishment offers hot meals, then they are often called a soup kitchen. Food banks usually provide a warehouse function for pantries, kitchens and other aid agencies like after school programs and senior centers. Maine has one food bank; Good Shepherd Food Bank, which provides food to over 400 organizations.

The idea of the food bank in the U.S. emerged in the late 1960s. A soup kitchen in Phoenix, AZ struggled to manage all of its food donations. A volunteer developed the idea of food banking to manage that inventory for that kitchen and other feeding organizations. During that same time frame, the Black Panther Party was developing its “Survival Programs” intended to support community access to basic resources. They developed initiatives including the “Free Food” program, which accessed and stored food until it was distributed in the community. Since then, hundreds of food banks have been established in the U.S. Dramatic growth occurred in the 1980s, for example, when the government made significant cuts in the Food Stamp program. Food banks, pantries and kitchens emerge in times of economic hardship when people lose jobs and incomes decrease. Food banks have become an accepted part of America's response to hunger. Some see the growth and increase in number of food pantries as evidence of active, caring community that is independent of the state. Others are concerned that food banks erode support for welfare programs that are designed to more equitably and efficiently meet the needs of hungry people. Emergency food aid has become “the new normal” for low-income families in financial crisis. Food pantries have become the default option as poor people are forced to rely on the charity of others when access to adequate income does not allow them to put food on their table. While people who organize pantries often do so with great commitment and sacrifice, they will testify that this emergency food distribution network has not been able to stall the steady increase of poverty. It is neither a sustainable nor a comprehensive solution to meeting the needs of hungry people. While our Council supports the network of 50 or so pantries in Cumberland County (noting that a few operations open and close each year), we agree that these should be viewed as a temporary solution. Our nation and our communities must organize our economies to achieve the goal of consistent access to nutritious food that is each person’s right. I have bad news friends.

Our food system is broken. • In the U.S., chronic diet-related diseases cost $500 billion annually • Agriculture is the main source of water pollution in America. • Over the past 10 years, only one U.S. state has seen a greater increase in very low food security than Maine. These data points only skim the surface. Our food system isn’t only broken for those who eat. It’s broken for the sacred souls who grow our food. It’s broken for workers throughout the food chain who make and bring us our food It’s broken for us all And here, today I am ministering to a congregation - you - that for the most part, knows this sermon. Most of you invested a lot of time and traveled great distances through wind and pouring rain to be here out of a desire to heal the food system. Still, I’ll remind you again. Our food system is broken. It is my belief and my unrepentant prejudice that the original sin of our food system is hunger. In this land of plenty, –if we’re being honest–ours is a land of privilege, flamboyant excess and waste, that we allow one person, whether they be able-bodied, child or elder to go without adequate, nutritious food implicates us all in a vast criminal conspiracy We can choose different priorities and organize our communities in ways so that everyone knows the care and nurturance of wholesome food but our imagination fails us and a fear of scarcity rules us. I’ll say it again: Our food system is broken. “Why does he keep repeating that?” To remind myself that we are the chosen few. We have been called. We are the ones riding the front of the wave that could crash at any moment and toss us into unwelcoming waters, while the majority of our comrades enjoy their Pringles and Frosted Flakes, with the assurance that Coca Cola “opens happiness” “adds life” “is the real thing.” Without the help of Chef Boyardee and Aunt Jemima we aren’t making nearly enough food for ourselves. It’s hard research to do, but I’ve heard estimates ranging between 8-15% as the quantity we are able to feed ourselves in Maine. So if that bridge between Portsmouth and Kittery crumbled or got blown up or the price of fossil fuel factored in what it truly costs us to use it there would be a lot of desperate scrambling –perhaps much less food waste– and a whole lot more people intimately familiar with food insecurity I attended a meeting with a political candidate recently, and tossed off that assumption we share “Our food system is broken” like it is common knowledge. The conversation tried to move across the table but he turned right back to me and asked, “How is our food system broken?” I nearly choked on my Holy Donut, startled by his sincerity more than anything, and not even sure where to begin. That fellow is going to be my mayor in a few weeks And he is a pretty smart guy. That tells me we have a huge public awareness campaign to organize. And I hear the refrain “But I barely have enough time to tend to my current job description.” “Our food system is broken” and sometimes I want to cry, not for myself, but for shame about the mess we are leaving our children and grandchildren. I want to shout, but not condescend, to the people who don’t have the knowledge and information we have. Because with a little awareness comes great responsibility and for those of you who aren’t covering your ears and going “La la la la” I’m sorry for forcing you onto this raft that is drifting toward the falls of an inevitable food system transformation. It’s up to us what happens as the raft disappears into the mist. I’d feel worse if I was telling you some news you did not know “Our food system is broken” and I look out at you, my friends, and feel great strength. Young and old Women and men Middle class… and upper middle class White and … white And despite gaping holes in this group’s diversity which will be critical to fix if we are to truly solve hunger We complement each other. We can complete each other. Let’s be careful about complimenting each other too much and invite new eyes and voices to our tables who bring us the blessing of discomfort and the gift of dissent. I am confident that starting where we live, shoulder to shoulder with our families, friends and neighbors not only can we begin, we have begun to heal our food system. There is amazing work happening in our communities, in our state, in our region. Let me correct that: You are doing amazing work in your community, in our state that is impacting the region and the Nation. Today, dearly beloved, we have gathered to push harder and farther than we have been • in restoring our shared food system, • in reconnecting to our sources of vitality, • in making ourselves and our communities whole. Let us not take this blessed day for granted but embrace its possibilities, leaving it all on the field as that cliché goes, not a field of sport or battle, however, but a field where we plant the seeds that will grow into the best future we can imagine for ourselves and can be harvested again with joy by those who follow us. Spoken by Jim Hanna |

Cumberland County Food Security CouncilThe CCFSC is made up of engaged citizens, community leaders, and representatives from local organizations that are leading the fight against hunger in Cumberland County and across Maine. Archives

June 2020

Categories |

Cumberland County Food Security Council 111 Wescott Road South Portland, ME 04106 [email protected] 207-939-3854 |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed